Happy Spring/Autumn, depending on where you are on the globe! Here in England, daffodils nod in wide beds beside roads, primroses fill graveyards, and violets, easy to miss because they’re so small, are giving way in the woods to anemone. The birds are loud and busy. I’ve just learned about the app Merlin, that helps you identify the birds singing around you, which is lovely, if rather a drain on my data.

What I Read

Because I spent my 20s and 30s reading 19C literature, I’m only now catching up on more recent gems. I was certainly late to the party with T Kingfisher, but what a wonderful novel was Nettle and Bone by T Kingfisher. This book ticked so many boxes for me – a heroine who’s anxious and awkward but pushes on to her quest, creating things from bones; powerful crones; blessings and curses; a goblin market; mysterious saints and gods. The touches of deranged humour didn’t derail the seriousness of the plot, which kept me reading and reading until it was over and I wanted more, now!

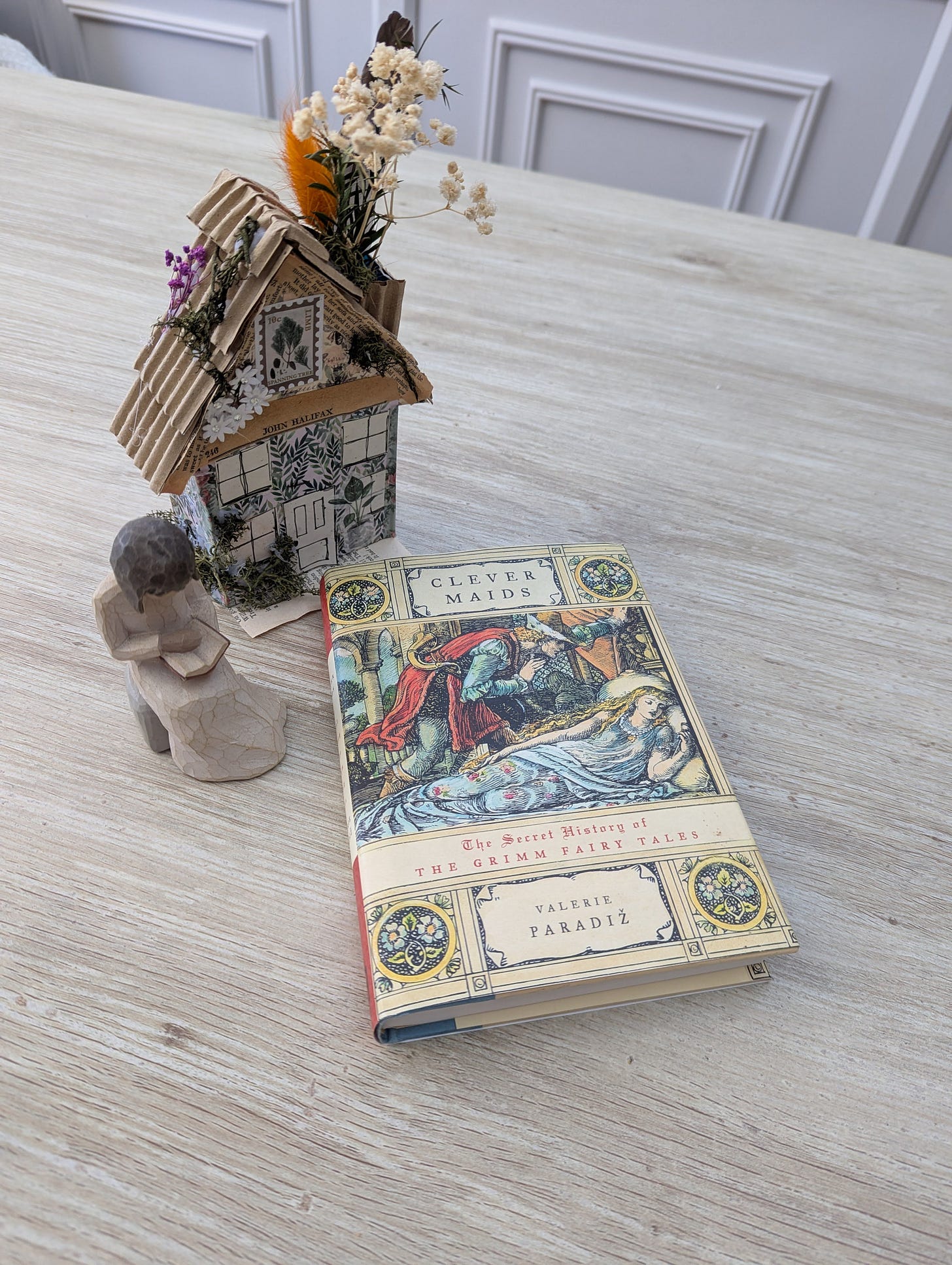

I also found Clever Maids: The Secret History of the Grimm Fairy Tales, by Valerie Paradiz an interesting read, and demonstrates how contributions of the various women in the Grimm brothers’ lives mirrored their own circumstances, although there wasn’t as much detail about them as I’d hoped. For instance, I feel for Lotte, the only sister in a household of boys, left on her mother’s death to cook, clean and launder for all of them and be moaned about by Jacob. But I did gain more of an understanding of the extent to which the Napoleonic occupation of the Germanic countries and their neighbours affected the lives, fortunes and passions of the brothers. It was a difficult time, and perhaps, in conjunction with their Calvinism, it’s not surprising that they favoured stories that ended with harsh justice.

I’ve learned, sadly, that a love of folklore doesn’t automatically mean I’ll love folk horror novels. I’m not into naming books I didn’t love, but this month’s least favourite read prompts me to ask my readers a genuine question about folk horror as a genre. It seems to be a popular trope for the protagonist to discover that the evil they’ve been unmasking is not only rooted in society and set to repeat all down the years and into the future for eternity, but is also opening its arms to the protagonist, who in the end walks into the embrace. I’m a sponge when it comes to the moods of things I watch and read (as well as the people I love) and I find the atmosphere of triumphant evil really depressing. I want to read stories where protagonists fight hard against bad things and finally win a triumph of some sort. In a world where we often see injustice, hate, fear and stupidity hold sway, surely we need stories of hope? Can anyone explain to me what the satisfaction is of seeing evil triumph?

Where I Went

We had a short break in Bristol recently. We viewed the Clifton Suspension Bridge, a wonder of Victorian architecture across a gorge. We explored the SS Britain, another wonder of Victorian engineering, that cut the voyage to America from months to weeks by using a screw propeller instead of sail – although it rolled a great deal, so I wonder if the passengers felt the subsequent sea-sickness was worth the cut in journey time? And we visited St Mary Redcliffe, which boasts a splendid community of gargoyles running amok over its turrets and towers. There are plenty of funny faces inside, too, including figures straining to “hold up” pillars, and a bearded man looking most alarmed at being depicted on an effigy. A fellow author, Owen Knight, tells me there are green men there too, which I totally missed, sadly. Well, I shall have to go back again one day. Why the obsession with gargoyles, you may ask? I have a completed children’s novel where they play an important part. It’s resting between rounds of agent submissions at the moment.

What I Wrote

March was mostly taken up with a writing course I studied on: Curtis Brown’s Gothic and Supernatural Fiction. It’s the second Curtis Brown course I’ve taken, and they’re well run and informative – and can be quite intense! I started three new stories from scratch to fit the different homework tasks, and now have even more unfinished projects on my drive!

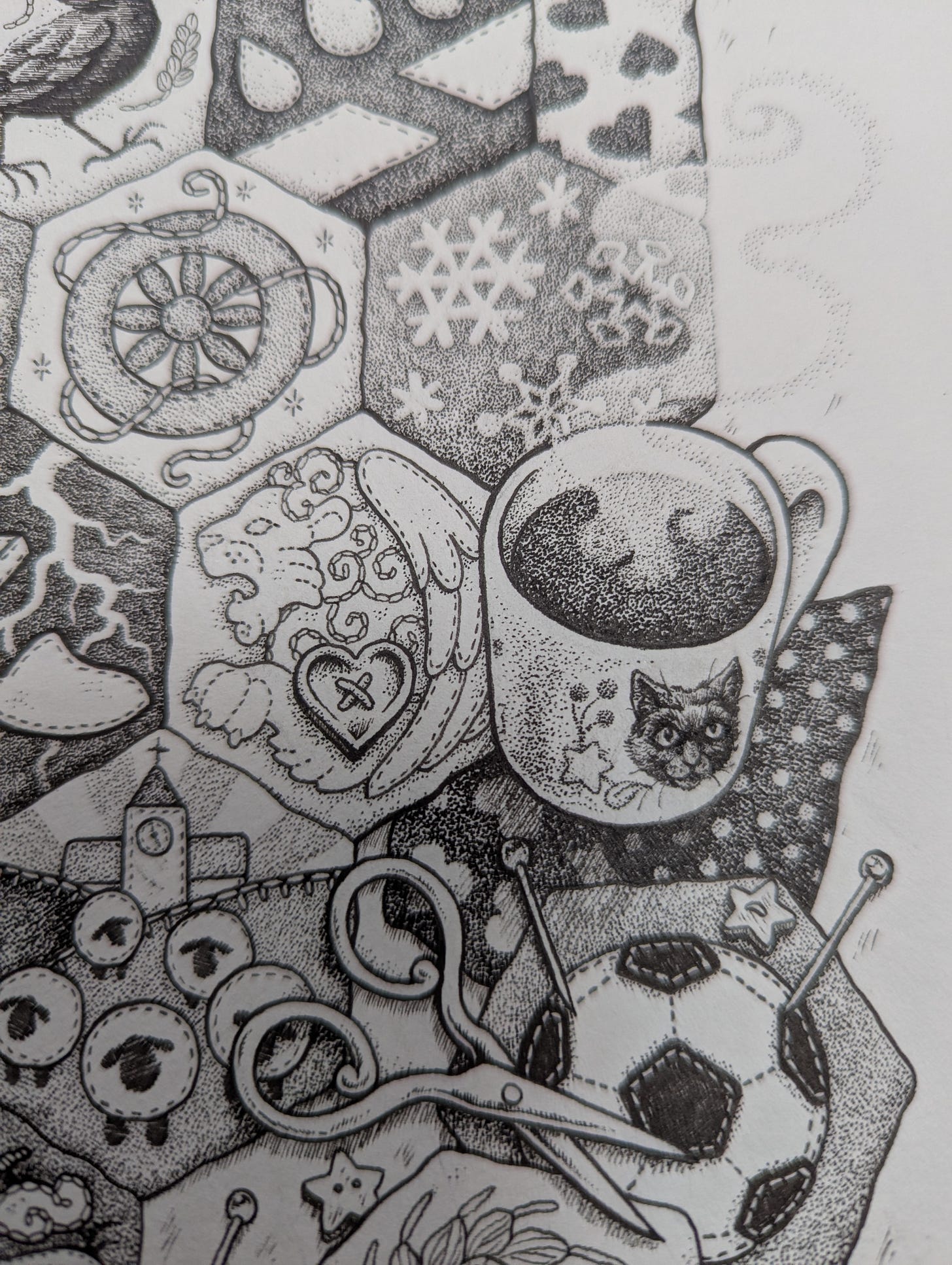

Meanwhile, emails went back and forth between me and my illustrator, the very gifted Emma Howitt. I am now delighted to say I have six small illustrations and one frontispiece for my story collection. Emma’s idea for the frontispiece is delightful. It shows a patchwork ( referencing the first story) where each patch hints at a different story. Readers can enjoy working out which is which. She also added a tea mug and asked me what I’d like as the picture on it, so I chose the cat we lost last year, Molly, who was the best little black cat ever. The next stage is to sort out a cover design.

A number of the stories have already appeared in online journals or in anthologies. If you follow publishing news at all, you’ll be aware that recently thousands of writers discovered that, not only had their books been uploaded onto a huge pirate website, but that Meta has used this to train their own AI, without permission from or compensation for authors. One of the anthologies I’m in is among these texts. Shame on you, Zuckerberg. If you want to support real writers (who aren’t billionaires), look out for my story collection, which I promise will be very affordable, and of course, please buy your books from proper sites or stores, or use a library.

Speaking of individual writers, if you like stories that are playfully macabre, check out my friend’s collection of short horror, Where do the Dead End Up by Priyanka Nawathe, available as a Google book. Yes, I know, it sounds inconsistent when I’ve just said I’m disturbed by folk horror. These stories are all gleefully light-hearted.

Fairytale Character Sketch

I didn’t explain this new feature well in my last newsletter. The idea is to talk about a minor character in a fairy tale and their role, rather than talk about a minor fairytale. This month, I’m choosing the old man in “Sleeping Beauty”. If you’re thinking, “What old man?” it proves my point that he doesn’t get much attention.

The version we tend to know is based on Perrault and Grimm. Their versions are similar but not identical.

In Perrault’s version of the story, we then skip forward one hundred years. There’s a new king of the country, and his son happens to be out hunting in the region where the briar-guarded castle lies. He can see the turrets above the hedge and asks around as to what hides there. (Angela Carter’s translation says he asked the local police, which makes me imagine him questioning men in blue with truncheons.) They have a host of answers – a ruin full of ghosts, a meeting point for witches, a safe place for an ogre to enjoy in peace his feast of children. (Perrault seems to have a bit of an obsession with ogres.) As I write this, I realise there’s a wealth of Sleeping Beauty spin-off stories here. However, an old man tells the prince a story he got from his own father, and relates the story of the princess sleeping for a hundred years till the destined prince wakes her.

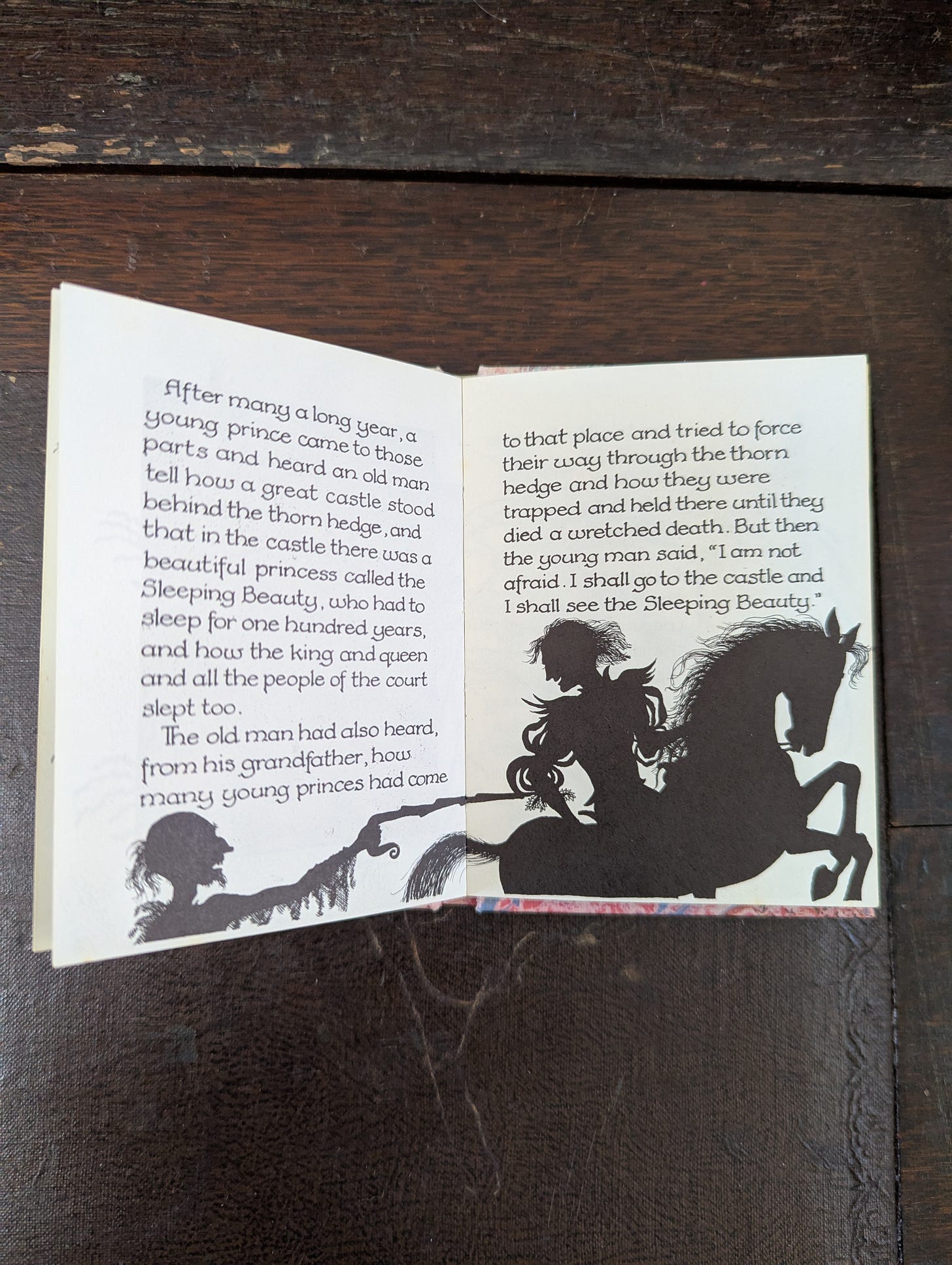

The Grimm version covers the castle so entirely that even the flag on the roof has disappeared behind thorns, and instead of grisly theories about ogres, we learn that rumours about the sleeping princess have led to princes trying to get in, being trapped by the thorns and dying miserable deaths. Many years pass, and a prince overhears an old man talking about what lies behind the briar hedge. The old man recounts what he’s learned (from his grandfather, rather than his father) of the princess and the hundred years’ sleep and the sad fate of the princes who tried to win through to her and failed. When the prince says he plans to try the adventure, the old man tries to dissuade him, but the prince perseveres.

There’s nothing more about the old man or his relation to the story. His role is to relate the story to the prince, who would otherwise ride on by, and in Grimm to try to dissuade him. The fate of the princes before our prince, and our prince’s determination despite the old man’s protestations, heighten the drama and the sense of this prince being worthy of the adventure and the princess. I like to think of the old man dining out for years on this story, telling it in the tavern to appreciative ears.

'Can anyone explain to me what the satisfaction is of seeing evil triumph?'

Evil's triumph is not for our satisfaction but our warning. Personally, I'm like you and want a hopeful ending I can aim at, but maybe the hope in tragedy is that you the reader didn't die or fail so hideously; we have a chance not to follow suit, and the trauma of suffering through the fictional failing is the shock we might need to keep us from the same fate.

Or it could be merely gratuitous drama and a matter of taste.