May has taken me by surprise. Each year I resolve to get up in time to watch the sun rise on May Day, or to find a local folk celebration. Each year I fail. This year I spent it indoors, doing a Pilates class then the weekly shop. I did find time to search out some bluebells. Like a nearby tree, they’re bursting out of old graves. It’s all very like the folksongs where trees grow out of the lovers’ hearts and intertwine above their burials.

Where I Went

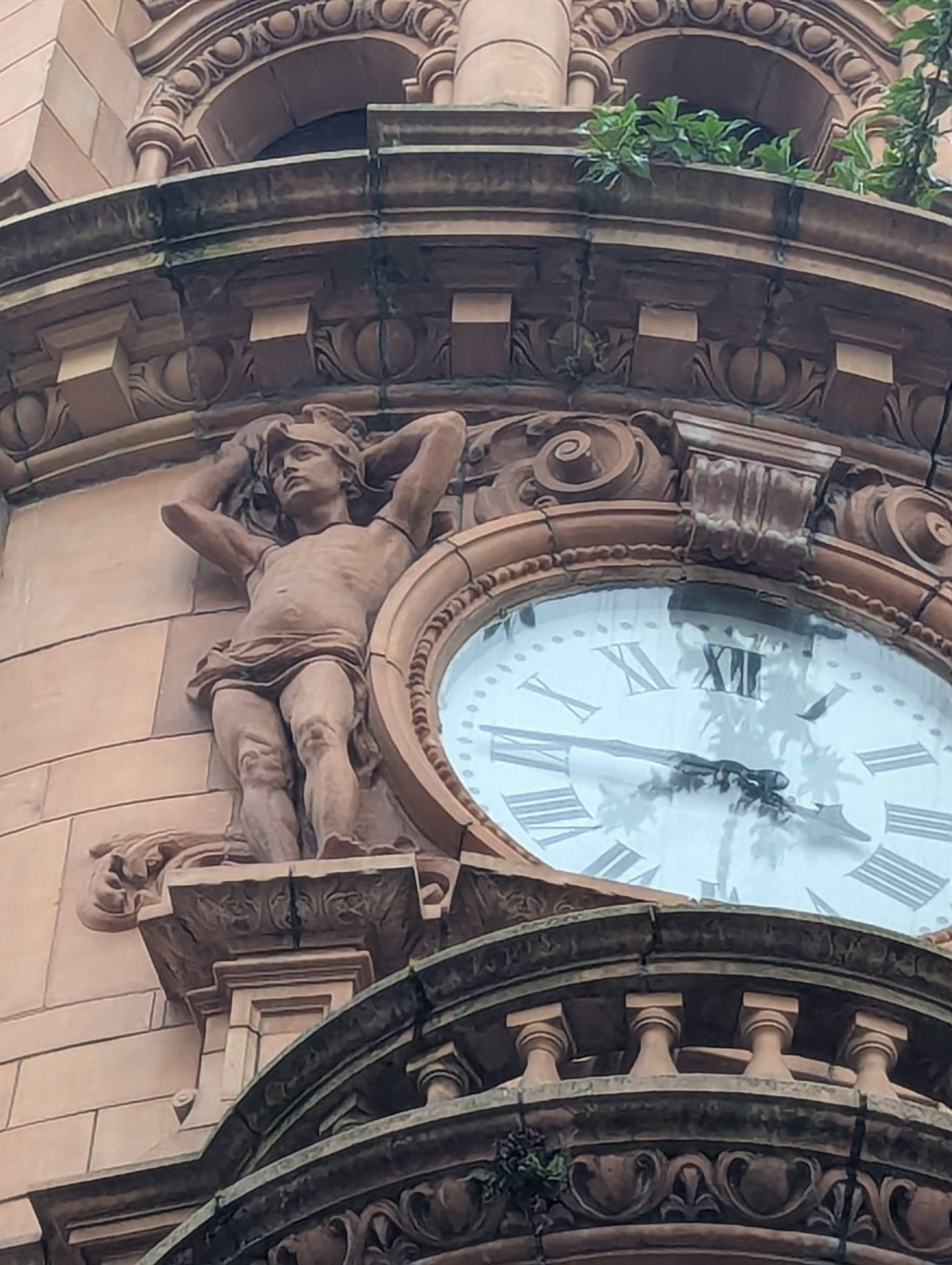

I spent a few days in Nottingham, once the city of the notorious Sheriff who locked swords with Robin Hood, now home to our daughter. Robin Hood seems to have settled down to everyday life: signage indicated he now runs an insurance company and also, at the weekends, a hot potato van. There was still plenty to see, though, for the seeker of stories, for instance the many figures and fabled creatures that lurk above our head in the architecture. “Always look up,” said the father of my protagonist in one of my middle grade manuscripts. “You’ll be surprised what you see.”

There was enchantment indoors, too, in the form of a mechanical clock – I adored the squirrel pushing a wheeled nest – and in a shop window clearly designed for Queen Titania and her friends.

Whilst it always seems a let-down to return home after visiting somewhere interesting, it’s good to remind ourselves of the interests on our doorstep. Our local city, Southend, isn’t very exciting if you step off the bus or train, or out of the car park – it looks just like most English high streets. But get off the main street and it’s a different story. There are so many parks that you can make a big ring round the centre using one after another, with stop–offs on the way to view a tiny museum housed in an old phone box, a 1960s fountain that interprets the traditional coat of arms of Southend, and a wealth of wall murals.

What I Read

My top read for this month was bought in Nottingham’s Waterstone’s.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson

A bit of a risk to pay so much more for a fabulous cover, but it paid off. What an unsettling story! **SPOILER ALERT ** Jackson led me cunningly up a path of sympathy with a sociopath, so much so that I actually felt relieved when the sociopath got what she wanted – isolation with her beloved sister in a wrecked house. And this, even though the clues as to who the murderer is are left scattered about for us to pick up if we want. I like that there’s still room for interpretation. Is the root cause of the village’s antagonism the murder, or the father? Is Merricat born like this, or was she abused? Does Uncle Julian actually suspect who the real murderer was?

What I Wrote

I’ve been hiding from the fact that at some point I need to format my fairy tale collection. Instead, I worked on revising a middle grade manuscript of mine that’s inspired by local folklore about a supernatural black dog, a portent of death. However, I now have a cover artist, so things are progressing. Meanwhile, my story “A Way Through the Briars” was published in Fairy Tale Magazine, in its Briar and Thorn edition. It was wonderful to be in the same publication as Caitlin Gemmell, whose Substack Ink-Stained Compass I follow and enjoy. I thoroughly recommend her Substack, her poetry collection True North and the Briar and Thorn edition for its many delightful or thought-provoking pieces.

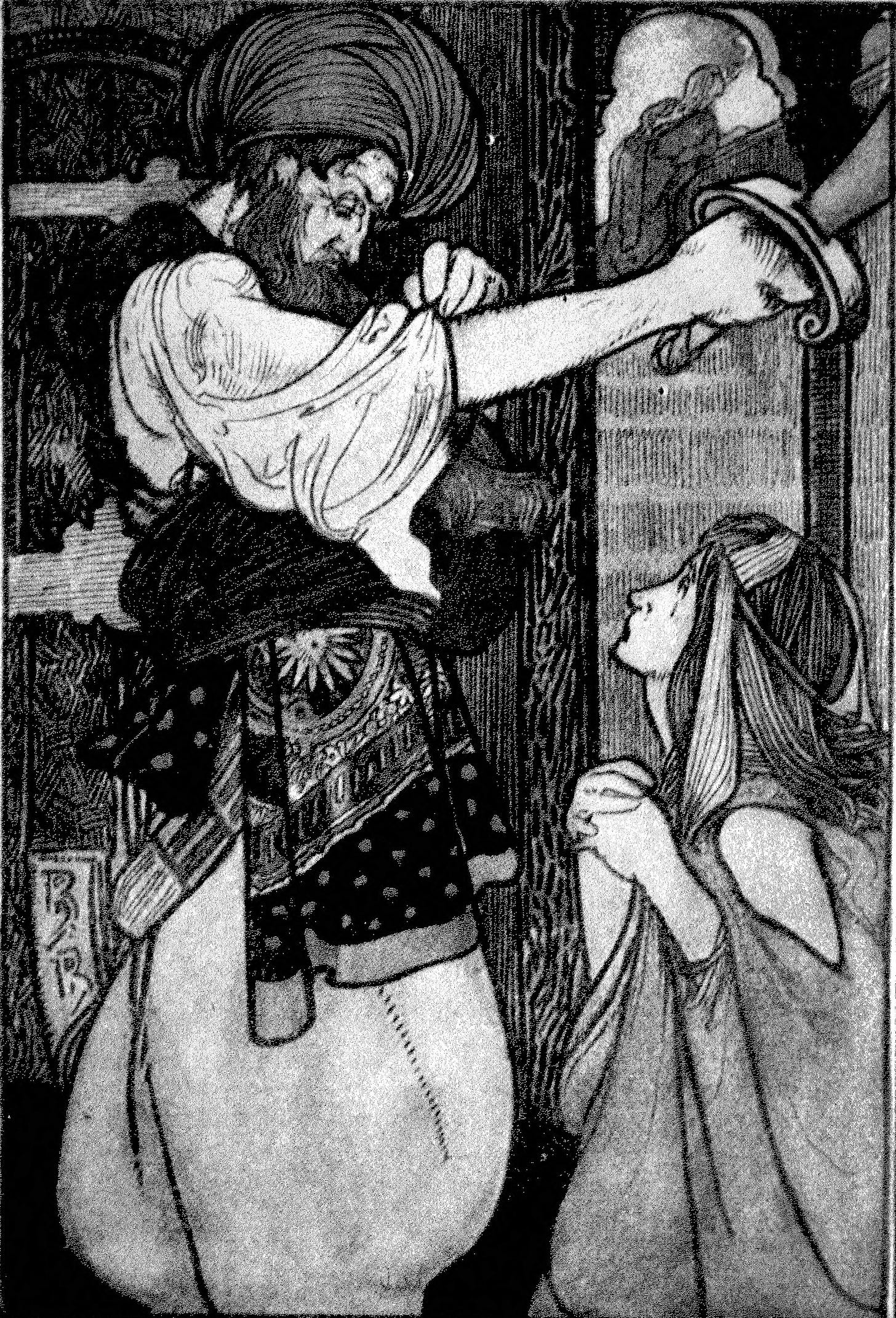

Fairy Tale Character Sketch — Sister Anne, in “Bluebeard”

With that title, she sounds like a saint or a nun, but in fact she is the sister of Bluebeard’s bride.

Looking carefully at the Perrault text, I was surprised on two counts.

Firstly, I went into my reading wondering if I would find a reason for the disparity of the names of the sisters. Anne is a European form of a Hebrew name, and in Christian tradition the name of the mother of the Virgin Mary, while Fatima is usually a Muslim name. What I actually found, however, was that Anne’s sister is not named at all by Perrault. Wikipedia helped me out here. Apparently the name is an embellishment to develop a concept that this story is set in the Middle East, perhaps because storytellers saw a parallel between Bluebeard and the Persian King Shahryār in One Hundred and One Nights, or perhaps from a feeling that a tale of such violence couldn’t possibly take part in refined France! So Bluebeard’s bride, like many a fairy tale character, is nameless. (I have a personal preference for keeping with nameless protagonists in fairy tales, rather than coming up with names for them in retellings, because I think when they are “the girl”, “the boy”, “the old soldier” etc, they stand for all the downtrodden young women, all the boys who are mocked by their family, all the people used up by society then discarded.)

My second surprise was how much of a role Anne actually has. I remembered her looking out of the window on her sister’s behalf, searching for someone to come to the rescue. But Anne plays a part from the very beginning, if you look carefully. (She isn’t named until the window scene.)

She is the elder of two sisters, daughters of a woman “of quality”, part of a larger family that includes at least two brothers. Bluebeard approaches the mother, not the daughters, and says he is open to either young woman as a bride. At first both sisters are wary, partly because of their aversion to his blue beard, and partly because of the stories circulating about his previous wives, who disappeared after marrying Bluebeard. They send him “backward and forward from one another”.

So Bluebeard ups his game and throws a house party, inviting the girls and their mother and other young people. A very good time is had by all, and the younger daughter decides Bluebeard isn’t so bad after all. We might conclude that Anne is not won over in the same way.

The story relates the marriage, and the departure of Bluebeard on “business”. He suggests to his new bride that she invites her friends over. I would assume Anne has come with the other guests, and joined in with the excited crowd that runs from room to room, admiring all the fine furniture, because the morning after the bride makes her terrible discovery and Bluebeard returns home, Anne is in the house. The bride sends her to the top of the tower to look out for their brothers, who are expected today.

The brothers arrive in the nick of time and slay Bluebeard. The bride’s fortunes have reversed, and she is now a wealthy widow. As well as using some of the money to buy her brothers commissions, she uses more to help Anne marry a young man who hasn’t much of a fortune himself, but who had loved her for a long time. We hope she loved him too. Was this the reason she resisted Bluebeard’s courtship when her sister didn’t? Or was she the more wary and sensible of the two? There’s no reason to think she saw the bloody chamber herself, but I do wonder what nightmares the women sometimes had in the following years.