The tree is up, the presents bought. In a perfect, twinkly world, I’d be settling down now to read some classic Christmas stories. But in reality there’s the wrapping to do still. But I can do that with my Christmas music on.

Not Bing Crosby! Or much that’s modern. My go-to music at Christmas is carols or songs with the feel of a legend, like “Good King Wenceslas”, particularly ones with links to books, of course. Here, I’m choosing four with a medieval feel.

The King who was a Duke

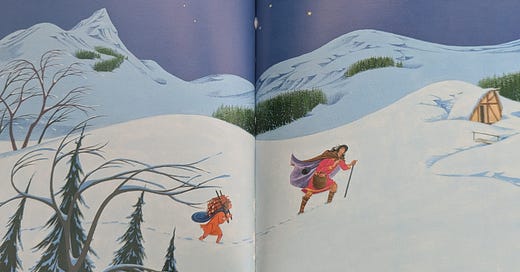

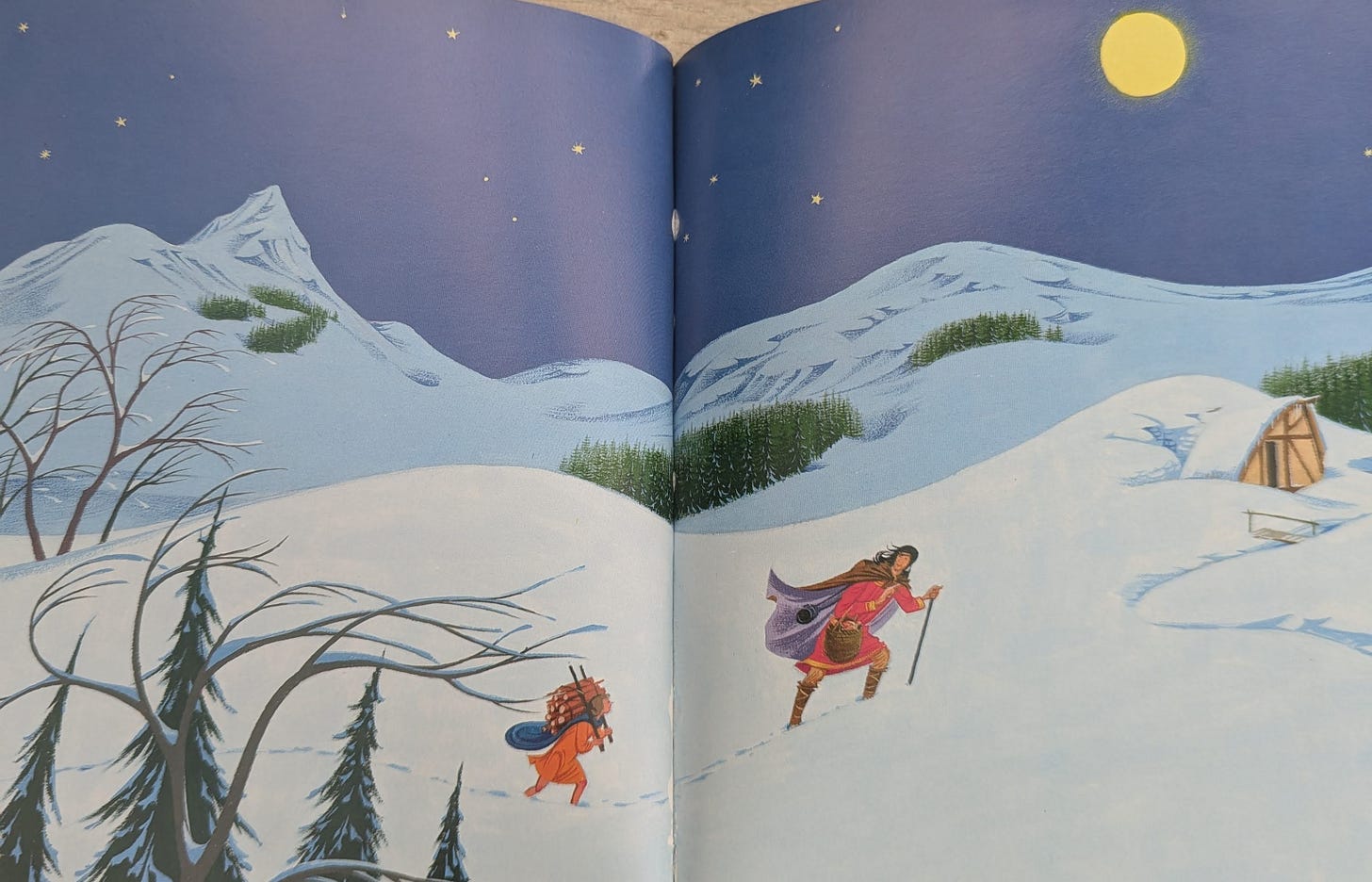

Wenceslas was real – Václav, really, as he was duke of the Czech kingdom of Bohemia, with his feast day being in September. A 12C chronicler tells of how he travelled barefoot in the snow with just his chamberlain to give gifts to the poor. According, however, to Good King Wenceslas (1987), above, written and illustrated by Pauline Baynes, queen of artwork for legends and fantasy, it is not Wenceslas but his page, Poidevin, who is barefoot, feeling no cold as he puts his feet in his lord’s footprints. In 1849 John Mason Neale published a version of this in Deeds of Faith: Stories for Children from Church History, then turned it into the carol “Good King Wenceslas” in 1853, adding the reference to St Stephen’s Day, or Boxing Day as we know it now. The Pauline Baynes edition includes the saint’s life and legends and the words of the carol.

The Kings who were Magicians (maybe?)

The Magi aren’t technically a legend, either, as they’re recorded in the Bible. But the brevity of the account has been a temptation over the years to add to their story. Were they kings? They seem to be wealthy. Were they simply astronomers, or were they astrologers and magicians? We don’t even know for sure that there were three, simply that they brought three gifts, rich in symbolism. (The carol “We Three Kings” spells it all out hauntingly.) I love the extra layers added over the years, brought out in paintings by the masters of the Renaissance. Each king represents a different stage of life – youth, middle age, old age – and each represents a different continent – European, Asian, African – because the Christ child came for all ages and all races. I love the names given them in later years, although there isn’t a consensus: I’m most familiar with the traditional Western names of Melchior, Caspar and Balthazar, but their names for Syrian Christians are Larvandad, Gushnasaph, and Hormisdas, for Armenians it’s Kagpha, Badadakharida and Badadilma and for Ethiopian Christians they’re known as Hor, Karsudan, and Basanater.

There are legends about their adventures after their journey to Bethlehem, and more about their bones after their deaths. For instance, the story of Babushka, the Russian woman who missed her chance to travel with them, was an intriguing discovery for me recently. I’m particularly fond of the story that Helen, mother of Constantine the Great, discovered them on her trip to the Holy Lands, because of her link with my adopted home, Essex. According to Geoffrey of Monmouth she was daughter of Coel, King of Essex, immortalised as “Old King Cole” in the nursery rhyme, and said to be the monarch after whom the city of Colchester is named. So did an Essex princess gather the bones of three ancient kings? There’s an English fairy tale about a princess simply identified as the daughter of the King of Colchester, who has a bizarre adventure that includes combing the hair of three heads in a well…If this sort of strange mishmash isn’t to your taste, there’s TS Eliot’s vivid “Journey of the Magi”:

“...the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes…”

And of course the Magi feed into various Christmas traditions, from giving out gifts in Spain to the Twelfth Night celebrations of the past, before we decided we needed to get back into our offices the day after New Year.

The Courage of a King’s Nephew

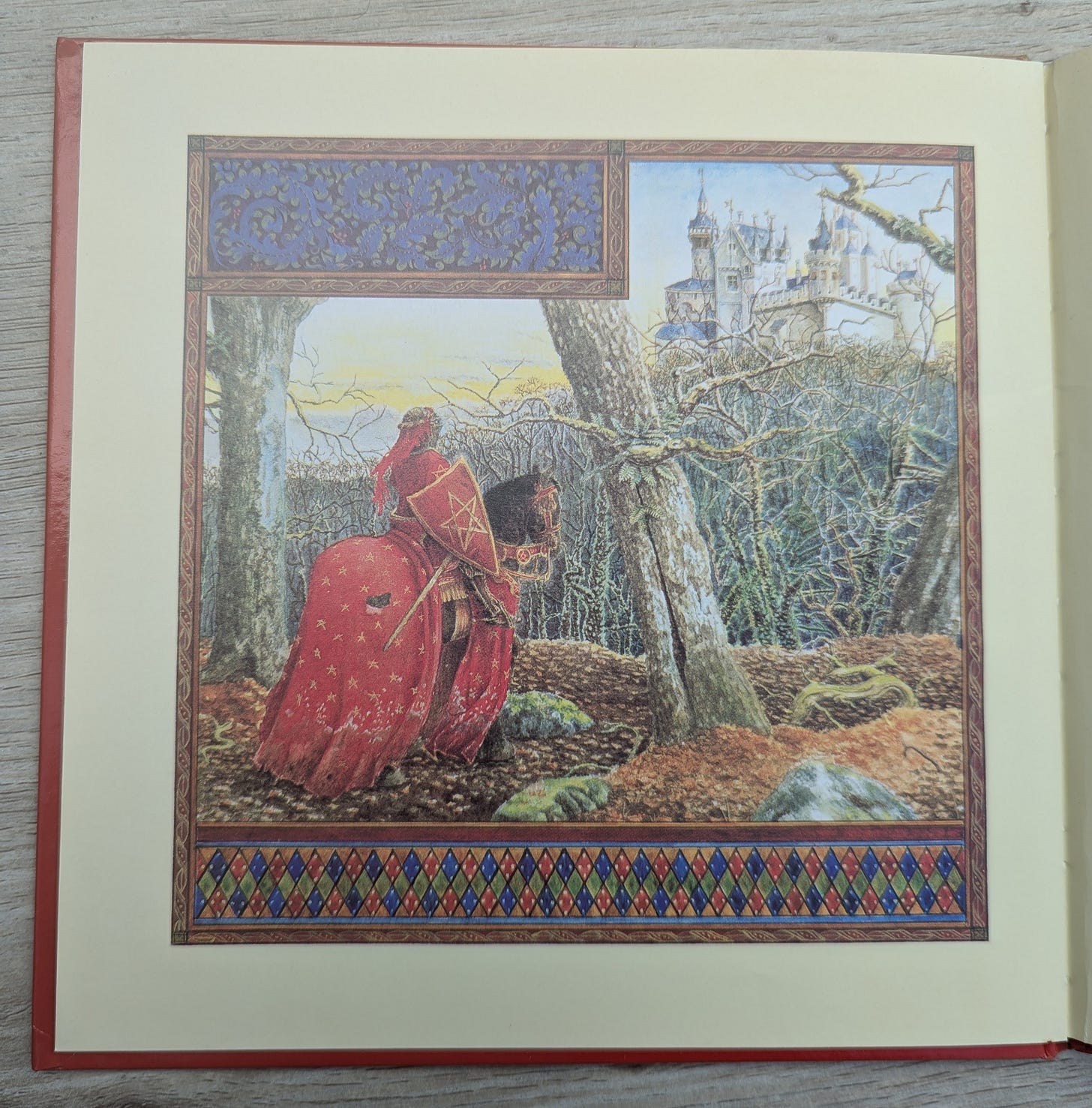

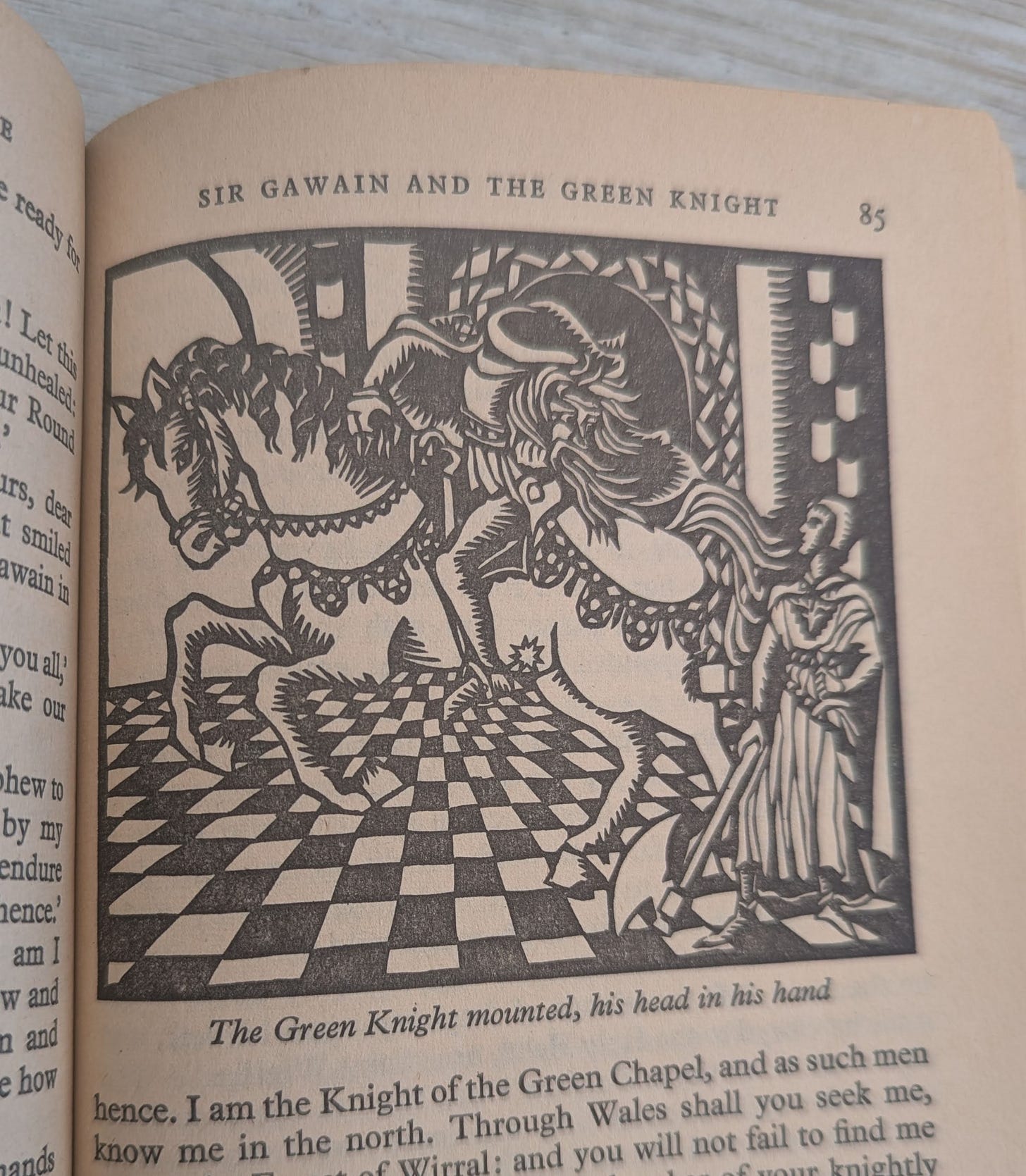

Gawain and the Green Knight is straight up legend. The edition I’m illustrating here sings with colour like a medieval illuminated manuscript, but my first encounter was through Roger Lancelyn Green’s splendid King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table (1953), with the elegant woodcuts of Lotte Reiniger. Gawain’s character varies wildly across different stories about him, but his two chapters in Green’s retelling show him as courteous, thoughtful and brave. And imperfect, as this story shows. There’s lots of speculation about whether the Green Knight is the Green Man, and/or an ancient fertility god, but I’m most taken by the mortal Gawain who takes up the beheading challenge to save his uncle Arthur, even when he knows that he won’t be able to replace his head like the gigantic Green Knight does. It’s not just his bravery that appeals to me, but also his weakness, as he struggles with the temptation to get out of the pact he’s made with the giant.

Cows, Sheep and Donkeys

Finally, a folk tradition with a medieval feel, although it might not be as old as that. There’s a traditional belief that animals kneel, or even gain the power of speech, at midnight as Christmas Eve turns into Christmas Day. Thomas Hardy wrote a poem, “The Oxen” based on the former. For the latter, there are various, sometimes rather violent, folktales about what happens when a set of animals is able to talk, and plot. There’s also a carol, with words by Robert Davis, called “The Friendly Beasts”, published in 1934, in which the animals round Jesus’ manger talk of their role in his birth. There’s a theory this carol is based on a 12th C Latin song for the Feast of the Donkey, which commemorated the flight of Mary, Joseph and Jesus into Egypt.

My first encounter with the legend was through Rosemary Sutcliff’s The Armourer’s House (1951). This tender, gentle children’s novel has a different feel from her later works with their stark poetry and tragedy, although there’s a thread of sadness running through The Armourer’s House too, because Tamsyn is struggling terribly with homesickness, while the family she’s living with desperately miss their oldest son Kit, who was lost at sea. It’s set in the reign of Henry VIII but references various folktales, including the one of the animals kneeling on Christmas Eve. Its final chapter is a triumph of hope and joy as Christmas Day breaks through.

The Marketing Bit

Tapestry Unravels is the title of my forthcoming collection of stories inspired by legends, folklore and fairy tales. I’d really hoped to put a Christmas-themed story in it, but decided against including a version of the Beast Bridegroom story, one of my earliest forays into the world of reweaving old tales, because it’s not original enough. However, there are snippets I’m very fond of, and I share one here with you. My heroine, questing to find her groom, who’s turned into a goose, has encountered the Magi, one by one:

"I saw such a creature fly overhead two days ago," said Balthazar, "He was flying west.

Then the king looked into the camel's pack and brought out a nutcracker and a bag of nuts.

"I bought these on my travels," he said, "They are magical. When you crack one open, it gives you what you need just at that moment. Try one now."

The girl took the strange carved nutcracker with its green jacket and its great frightening jaws, and cracked a nut. Out of it fell a fur coat. She put it on and went on her way.

I rewrote this story over and over until I had a completely different version which will go in the collection. Originally published in From the Stories of Old (2016), it’s called “The Goose and his Girl” and while there are no nutcrackers, it does feature a frost fair.

Stay tuned for further news!

Fascinating review of seasonal folklore. The relics of the Three Kings are supposed to lie up the road from me in Cologne, Helena having taken them to Milan, whence they were brought to Cologne by Frederick Barbarossa.